I wanted to be a farmer growing up. I still want to be him.

Remembering my childhood hero, Mr. Barley.

Entering the waiting room, I appraised the situation: plastic chairs surrounding an expanse of vinyl flooring, and a check-in station to the left. Par for the course. After talking to the nurse, I squeaked across and took the chair next to a good ole boy in button-down and slacks, leaving a seat between us. He sat and scrolled, and from time to time, would lean over to his wife, showing her a video and whispering commentary in her ear. She would laugh, and sometimes whisper something back before and they’d slip back into easy silence. It took me a minute to realize how immediately I had admired them.

A few minutes later, the spot between us was filled by a pair of mud-stained blue jeans. Here was another character, with a different kind of moral authority. Hands resting palms down on his pants, he stared straight ahead at the wall through which he had just come, waiting for his name to be called. He looked like he had come from work, and would be going back to work. Again, an immediate gut reaction–this time, trust.

* * * * *

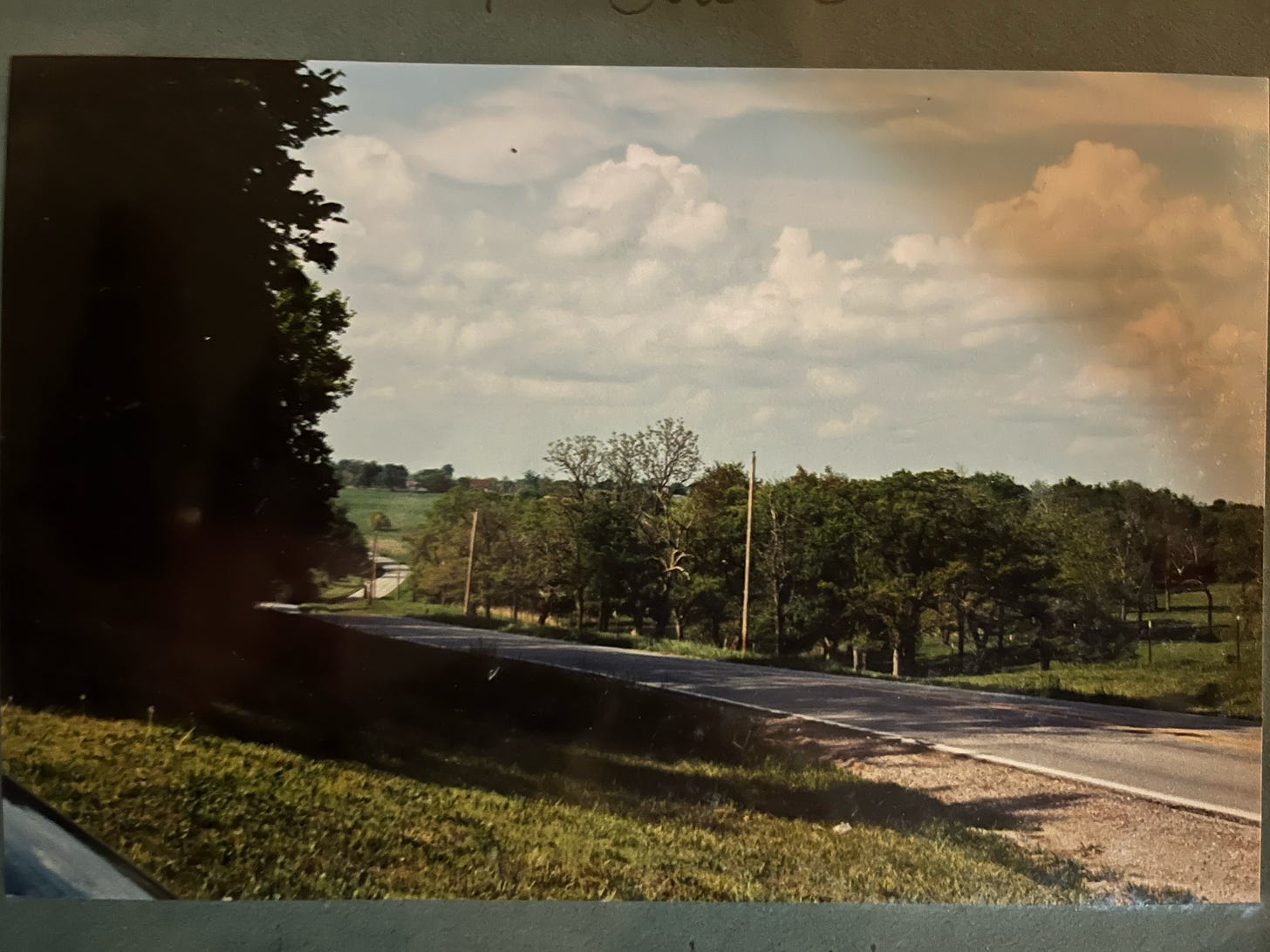

Mr. Barley and his wife, Doris, lived across the road from our blueberry farm in a white one-story surrounded by cows. From our gate, I would watch him move between the house, outbuildings, and fields with the calm assurance of a man taking care of responsibilities. He had a job to do, and as anyone who has been around farmers knows, that job wouldn’t be done until his son had inherited the place.

That inheritance was on the horizon, though. Even at seven- or eight-years-old, I narrowed my eyes at Mr. Barley’s grown up son, suspicious of anyone whose arrival was foretold by fallen trees and bulldozers. Mom was adamant that the new construction, glistening in its apparel of unsullied siding a few hundred yards from the old Barley home, was nice, so nice. The son, with his SUV and juris doctor, was also nice, so nice. But I knew something was afoot.

Every June, Mr. and Mrs. Barley would have us over to their place to pick peaches. Mom and Dad would grab a few straight off the branch while we kids separated the wheat from the chaff among those that lay on the ground. And all the while, Mr. Barley would stand there rocking heel-toe, toe-heel in his boots and overalls, letting Doris and the change in his pocket do the talking. He wasn’t reticent, just shy, more accustomed to converse with livestock than his closer, close-talking human relatives.

He could be loud, though. We knew because we had heard him from across the road. Morning and evening, he’d walk to the fence overlooking the pasture and bellow out his vocal equivalent of wooden-spoon-on-skillet. The Holsteins would come up across the bluegrass, slowly but surely, ready to be fed.

* * * * *

What had begun as mild curiosity had swelled into an overpowering question: Who, in heaven’s name, was bellowing like that? With some worry, I realized that the sound was coming from the direction I would be asked to go when the nurse called my name. Furthermore, it seemed to be the voice of a medical professional.

“Alright, now…IN!...two, three, four…OUT!...two, three, four…IN!”

What all of these commands had to do with routine blood work was unclear. Repetitions of the words IN and OUT are hardly the words that someone–let alone someone with a live fear of needles–wants to hear while waiting for his turn to be pricked in some back room of the hospital laboratory. And yet those two words seemed to constitute the lexicon of the veritable Wizard of Oz blasting from behind a nearby curtain of sheetrock.

“IN!….OUT!…GOOD!...IN!...OUT!

You’d think he was a drill sergeant, stationed just outside the recruitment office to test the mettle of army-hopefuls. I glanced around the waiting room. I was greeted by shared concern–that is, until I looked to my right. Button-Down had looked up from his phone, but, if anything, seemed to be enjoying the thunderous intrusion. Mud-Stained Jeans was staring ahead as before, but grinning ever so slightly. I decided to think the drill sergeant was less worrying and more entertaining.

Then, from a room directly across from the aperture into which my waiting room compatriots had been disappearing, came a wild-eyed patient–male, around sixty years, with long gray hair–accompanied by a doctor in black scrubs. The doctor was pushing a rolling medical apparatus that looked something like a metallic coatrack–I can only guess it was some sort of portable ECG machine–and between the patient and coatrack ran several tubes. The patient stumbled into the middle of the waiting room, looking from one face to the next with a helpless, pleading expression, giving the distinct impression of an animal being led to the center of a ring by a circus-master. And then the circus-master bellowed again:

“TO THE RIGHT! THE DOOR TO THE RIGHT! INTO THE HALL! NOW BREATHE IN!…two, three, four…OUT!...two, three, four…and IN!”

They departed through the doorway, but it was a while before the voice did the same. The nurse hadn’t looked up from her computer.

* * * * *

Each Christmas morning, the Barleys would come over for coffee cake and quiche. I remember that, because I remember Mr. Barley saying he’d have his coffee black. I haven’t lived up to the silent vow I made that day, but I still consider cream in coffee a moral failing.

Looking a little stiff in a collar and clean pants, Mr. Barley would clean his plate while Doris told stories about Mr. Barley.

One Thanksgiving, he’d gone out to serve the cows their holiday supper when, failing to stoop far enough as he entered the silo, he had nearly lost his scalp to the razor-sharp edge of the door jamb. That year, they ended up eating Thanksgiving dinner at Doc Marsh’s, after the latter had finished stitching Mr. Barley’s head back together. Sure enough, following Doris’ finger across his forehead, we could make out the scar to prove it.

I don’t know if I can top that, but I have my own character-defining memory of the old farmer from direct experience. It was probably July or August–in any case, the day was hot and sunny–when all of a sudden the sky to the west went purple, and then black. Dad came tearing up from the direction of the chicken coop, gesticulating toward what was now a rapidly-forming funnel and yelling at everyone to get in the car. We lived in a modular home, so we didn’t have a basement, and the crawl space couldn’t fit all seven of us. So we piled in the van, thrilled by our apparent danger, and took the two-hundred yard trek to the other side of the road, where we, in turn, piled into the Barleys’ basement. Beyond that, all I can recall is sitting on the stairwell in yellow light, staring up at Mr. Barley, who stood guard at the top of the stairs, refusing to come down. Only Mr. Barley seemed to know how soon nature was going to take him, regardless of the storm.

I don’t know if it was because she had changed shape, or she knew the shape Mr. Barley was in, but one day Mrs. Barley gave Mom her square-dancing dresses: one, big red polka dots on white, and the other, red with little white dots. Back in the day she must have looked like a whirling, twirling strawberry with ruffles on the sleeves. In years past, they had gone dancing every Friday night, but now they mostly watched from their folding chairs and listened to the music.

When I was nine, we moved from the berry farm, but for a while we kept in touch with the Barleys, crunching onto their gravel driveway whenever we came into town. One of the last times, it was only Doris, but she was just the same, going on and on about him. Once the cancer had set in, things had moved quickly, but she was glad he was at rest. He had completed his chores, and he’d done a good job.

She sent us on our way with peaches.

* * * * *

When the voice of the circus-master had, at long last, evaporated from the room, we sat in silence for a couple of minutes. I could almost feel the wise-cracks welling to my right.

Button-Down looks over at Mud-Stained Jeans for the first time.

“I’ve been worked on by that guy. He sure gets excited. You’d almost think he wants to give you a heart-attack.”

Jeans leaves his gaze where it is, but allows the slightest shake of his head as he formulates his response.

“It’s clear he enjoys his job.”

That was good. Now it was my turn: ball cap and clean jeans. Hands in pockets, no change to jangle. Maybe someday.

“To think I came in here worried about the needles.”

It felt good when they laughed.

* * * * *

It’s strange to realize, at age twenty-nine, that you’ve spent the last twenty years seeking the approval of a man you haven’t thought about in nearly as long. In fact, it’s almost as strange as realizing that your hero, as a nine-year-old boy, was an old farmer who lived for nothing more than to make his wife and cows happy.

He probably never knew he cut much of a figure in my little imagination, and truthfully, I may never have realized that he did either, had it not been for two good ole boys in a waiting room. Side-by-side, they seemed to constitute, for a fleeting moment, one whole Mr. Barley, with his whispered devotion and honest labor.

Maybe remembering who you are is always a matter of remembering the person you want to be. These days, that person is nine-year-old me. He knew who he admired.

This was such an affecting and beautiful piece of writing, and quite moving, too. Really, really loved it. Thank you for sharing!