The best way out is always through the snowstorm.

Life is like a box of Tootsie Pops.

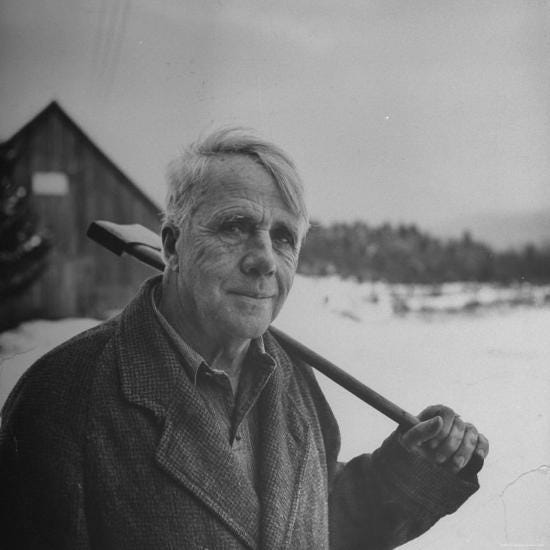

On a piece of copy paper hastily stapled to a bulletin board in my classroom are the following words, printed in a censorious Times New Roman: “The best way out is always through.” Beside that quote stands a hastily-stapled Robert Frost, with an axe on his shoulder and a grim sort of smile on his face, generally looking like he has just come from digging his own grave with the wrong farm implement. It is an image that seems to capture perfectly the kind of poet who could write a line as subtle and dark as “The best way out is always through.” Frost may be known for his preoccupation with woods–yellow woods and snowy woods and dark woods and birch woods and various other kinds of woods–but his real preoccupation was with his curious desire to die. He was the kind of poet who had to convince himself over and over that death, though a fate devotedly to be wished, was also a fate that had to be earned. For most of us, even those of us most convinced of a blissful afterlife, our existence is like a Tootsie Pop where life is the Pop and death is the Tootsie–a nice yet somewhat ambiguous something we’ll be glad to enjoy after the first sort of sweetness has been used up. Exactly how many licks will it take to get there? Honestly, we have no idea, but we’re going to try our best to enjoy each one in the meantime. But not so with Robert. Given the choice, he would have taken the Tootsie Roll plain, so as to avoid the pain of eating the Pop to get to it. Any child would eye such a character with suspicion.

Still, Robert Frost had a knack for summing up whole categories of human experience in the span of a few syllables, and in many a tight squeeze, I have seen him grin grimly in my mind and utter a quiet, “The best way out is always through.” For example, just last week, as I watched twenty eighth-graders filter into my classroom to take a test I had failed to print off, a melancholy wink from a copy-paper Frost provided me with just enough spirit to manage a faltering, “Hey kids…guess what? It’s a bonus study day.” A week later, I am glad that I opted for continued existence in that moment, and I probably owe something to Frost for that decision.

But Frost’s slightly more succinct and substantially less suicidal version of the phrase–“no way out but through”–is the one that has normally borne me up in moments of great fear and trembling. The next time you find yourself running a 400 meter dash, asking a chagrined father for his daughter’s hand in marriage, crapping your pants in public, or watching an episode of The Secret Lives of Mormon Wives with an insistent significant other, I recommend returning to the phrase. It will probably help. And above all, if, by chance, you find yourself driving in a blizzard through the Rocky Mountains on the night before Thanksgiving–remember Frost. The good news is this: If you do, in fact, make it out when there is no way out but through, Frost’s hollow black hell of a universe will have bestowed upon you one hell of a story.

- - - - - - - - - -

As we pulled up to the lady’s house, Lansing tried, once again, to explain how we–four irresponsible, roadtripping college buddies–could justify imposing on anyone on the night before Thanksgiving, let alone an Anyone that none of us had met before.

“Like I said,” said Lansing, wearily, “She’s the sister of my Mom’s former co-worker. Mom called last week and she said we could stay.”

“Did she know we would be arriving at 10pm?” asked Grayson, with all the premature maturity of a someday Navy Seal.

“I don’t know,” said Lansing, by which he meant, “No, we were supposed to have arrived hours ago.”

“Does she have a family?” asked Loyal, with all the wisdom-beyond-his-years of a Missouri farm boy.

“I think so,” said Lansing, by which he meant, “Yes, she has several small children.”

“Do you think she’ll let us stay?” I asked, with all the immaturity of someone who feels he should have a mature question to contribute, too.

“I hope so,” said Lansing, by which he meant, “I really, really hope so, because we are in Breckenridge, Colorado and a snowstorm is rolling in.”

It took the lady a few minutes to answer the door bell, and when she did, she had a huge blanket pulled around her shoulders that hung to the floor, so that the only visible part of her was an expression that didn’t look happy to see us.

“Hullo?” she asked, as if we might disappear if she pretended she didn’t know who we were. But we remained.

“Hi, I’m Lansing,” said Lansing. “I am your sister’s former co-worker’s son, and these are my college buddies: Grayson, Loyal, and Christian.” He paused to allow her to remember us, and when her face failed to offer any evidence of recollection, he bravely stumbled forward into the murky verbal beyond. “Uh, yeah, so…my Mom texted your sister, and she texted you, and you said we could stay here tonight.”

“If you’ll excuse me,” she said, and disappeared into the house. For five long minutes we stood on the doorstep, shivering and stamping into the alpine silence, and casually wondering what the lady’s name was and if her guest bedroom was warm. Finally, she returned.

“My husband says a snowstorm is coming,” she declared, clearly hoping the implications of this statement would not have to be explained. But we remained. We stood in alpine silence. Everyone shivered. No one stamped.

At long last, she offered a second interesting fact: “Tomorrow is Thanksgiving.” And then, after another bristling pause, a third: “These roads won’t be plowed for four days.”

We look at each other, speechless upon having witnessed such a dearth of hospitality. Would this lady really rather send us out into a Breckenridge blizzard than have her small children spend the next four days in our company? Would she really rather find us on the news tomorrow morning than find us in her house a few short mornings from now?

Then Grayson, mustering all of his premature maturity, put a point on things: “When does the snowstorm arrive?”

“My husband says you should be able to outrun it to Denver,” she said, by which she meant, “Goodbye.”

As we retraced our tireprints through Breckenridge and back to the highway, the first snowflakes began to fall, big thick flakes, and by the time we had turned onto I-70, it was collecting on the road.

“Let’s freaking go, boys!” said Loyal, and he cranked up the Springsteen as he urged his 2003 Mercury Grand Marquis to an ambitious 70 miles per hour.

I sat in the back seat, praying I’d live to see the lights of Denver, but also oddly exhilarated that I would have nothing to do with it either way and there was no way out of the Rockies but through a snowstorm.

- - - - - - - - - -

Of course, theoretically, we could have chosen to get snowed-in at an overpriced Breckenridge hotel, and perhaps, considering the possible costs, it would not have been such an overpriced hotel after all. But that hardly occurred to us until the snow had turned to sleet, and I-70 had turned to a sheet of ice, and our recent exhilaration had turned to complete and utter panic.

I remember white-knuckling the driver’s seat in front of me, as if I might keep the Titanic afloat if I could only grip the railing a bit tighter. Through the last iceless aperture in the windshield–no more than seven or eight inches in diameter–all I could make out were the red brake lights of a semi, and looking behind, there were only the liquid whites of a semi’s eyes. To my left–sure enough, another semi, careening down the 7% grade, all while boxing us against the darkness to our right, a darkness vast and vacant as an empty socket. Why those semi’s were on the road, I will never know, but how our Grand Marquis was still on the road is a question nearly as confounding. Angels, people–angels.

It was at that moment, precisely as the sleet was papering over our peep-hole of a windshield and the semi’s had hedged us up against the guard rail, that Phil Collins began to whisper the first verse of “In the Air Tonight,” and to my ears, his voice was the sound of a cold, steely universe, mechanical and impersonal and yet working all things toward the singular end of throwing our car off the cliff and down a thousand feet to the Colorado River below. It really was in the air that night–the fear of death, inevitable and looming and large, and the yearning for tomorrow that is the white-hot center of every man’s soul. And I realized, all of sudden, that Collins was right: I had, in fact, been waiting for this moment all my life, the moment when everything would be on the line, and only God would get to decide the outcome.

God, and Loyal, that is. While all of these half-baked philosophical musings were filtering in and out of my gray matter, a wise Missouri farm boy sat dutifully behind the wheel with his mind locked on the task at hand–or so I thought, until the end of the third verse, when Collins’ voice swells into an echoey anger and the whole world waits in breathless anticipation for him to take up his drumsticks. At exactly that moment, three minutes and forty-one seconds into the 2015 Remastered version of the track, Loyal lifted his hands from the steering wheel and performed the most dramatic, the most committed, the most downright perfectly-executed impersonation of Collin’s iconic drum fill that I have ever witnessed.

Lansing yelled, and I yelped, and someday-Navy-Seal Grayson reached for the steering wheel, while Loyal let out a euphoric “Let’s freaking go, boys!” for what wouldn’t be the last time that night, and, having regained control of his appendages and the wheel, lurched the car in the direction of the narrow gap between the semi to our left and the brake lights to the front. Angels, people—angels. Camels cannot usually go through the eye of a needle, but through God, all things are possible. We made it through. And as we emerged from behind that mobile wall of bright red brake light and the barrage of sleet kicked up from its tires, the windshield began to clear ever so slightly, and we caught our first glimpse of the golden lights of Denver glittering on the plain in the distance.

- - - - - - - - - -

I have never been so happy to pump gas in the bitter cold as I was when we finally arrived in the westernmost Denver suburb. We all stepped out and stood there beside the car, laughing and shaking our heads, mostly speechless, just reveling in the fact that we were alive enough to shiver.

And then it occurred to me: Tomorrow was Thanksgiving, and there was only seven hours of Kansas between me and my extended family.

“It’s only seven hours,” I said, by which I meant, “You suck if you say no.”

“Well, we’ve come this far without paying for a hotel,” said Lansing.

“It looks like the storm is still hung up in the mountains,” said Grayson, consulting weather radar.

“Let’s freaking go, boys!” said the excitable Missouri farm boy.

- - - - - - - - - -

We crashed at my uncle’s house for a few hours, and arrived at Grandma’s just in time to share what we were thankful for before dinner. All the relatives went around the circle, from person to person, and I don’t know what I said when it was my turn, but I know what I should have said–I should have said that I was thankful to smell Grandma’s stew simmering on the stove, and thankful to hear my little cousins thumping down the blue carpet stairs to the kitchen, hoping no one would notice that they were late for prayers, and thankful to see Pappap yelling furiously in the TV light with a Diet Pepsi in his hand, and most of all, thankful to have lived just long enough to have learned that this, this moment right here in the present, was the moment I had been waiting for all my life, and the next moment would be, too, and the moment after that.

I guess that’s why I think Robert Frost’s original quote, for all its morbidity, is worthy of the bulletin board in my classroom. In my experience, all it takes is one close brush with death—that is, with a moment where there really is no way out but through—to realize how much you want life, how much you would choose it, despite its mix up of happy and yet hard and here and yet homesick. How much you prefer it, far and away, over having never been born at all.

Because Frost is right: We do choose life. We choose it every day. Through is not the only way out, but it is always the best way.

P.S. If Loyal seems like a cool guy, check out his Substack.

You so vividly portrayed the real events of that fateful evening. Not to mention we were running on fumes as this was the completion of a week long trip.

Loyals drum fill will go down in the annals of Colorado history and I shan’t soon forget what insanity took place that day.

The only way out is through! Incredible writing my brother.